Margaret Hamilton - The Woman Who Put Men on the Moon

July 20, 1960. The American nation and people across the Earth watched in awe as Neil Armstrong made history by setting foot on the Moon. Today, almost everyone can recite Neil’s monumental first words on the satellite: “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” However, few people know that the landing of men on the Moon would likely not have been possible without the brilliant work of one woman – Margaret Hamilton.1

Margaret Hamilton was born on August 17, 1936 in Paoli, Indiana.2 As a child, she very much enjoyed school, but there was something about mathematics she loved more than anything else. Her talent in solving complex problems was noticed by her 11th grade math teacher, Mr. Phillips, who would later recall Margaret’s frustration with the lack of computer programming courses in school curriculums. “Math and Computer Programming are the foundation for progress”, young Margaret had said to him, as though she was able to see into the future. And little did anyone know, time would prove her right.3

Following her passion for math, Margaret Hamilton obtained a BA in Mathematics from Earlham College in 1958. While in college, she met her future husband James Cox Hamilton. Margaret had initially planned to continue her education pursuing a graduate degree in math, however she decided to first follow her husband to Boston where he attended Harvard Law School. Despite delaying her own education plans to support her husband, Hamilton was far more progressive than most married women at the time. For example, she refused to take part in a Harvard social tradition, which required wives of law students to pour tea for the men. “No way am I pouring tea!”, Margaret told her husband, asserting her rights in an era where women did as they were told. 3

In Boston, Margaret Hamilton took a job as a computer programmer for Professor Edward Lorenz in the Meteorology Department at the Massachusetts Institute of technology (“MIT”). Not having a formal education in programming, Margaret learned on the job, using the instructions for a computer called “LGP-30”. Shortly after, the “Apollo” program came along setting the bold mission to land men on the moon. Margaret enthusiastically pursued the opportunity and became the Lunar and Command Modules on-board flight software team leader.4 She was additionally assigned with creating the software for operation in case of mission abortion, because “she was a beginner” and because it was believed that the mission “would never abort.”3

Knowing that human lives were at stake, Margaret Hamilton worked tirelessly to create a software that would lead the mission to success. At the same time, she was also raising her daughter Lauren, who often ended up in the “Apollo” simulation room, playing astronaut while her mother was working. One time, as Lauren was playing with the simulator, the system crashed completely. Margaret quickly realized that Lauren had selected the wrong program, which in turn had the system confused. Concerned about the risk of this happening during flight, she sought permission to recreate an emergency situation in order to test the astronauts’ response. Her concerns, however, did not seem compelling to the project leaders who believed the astronauts were trained not to make such mistakes. Naturally, they were wrong.

Approximately three minutes before astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were set to land on the moon, an emergency occurred. Hamilton’s software, which no one thought would ever be used, came into play. Since she created the emergency program herself, she became the expert who saved the day. Relying on her confidence in the program – a product of the rigorous testing process she used in her work – NASA authorized the landing and the mission became a success.

In 2016, Margaret Hamilton was honored with the highest civilian award in the United States, the Medal of Freedom, by President Barack Obama.1 Today, Margaret is the CEO of “Hamilton Technologies” Inc., a software engineering company based in Cambridge Massachusetts, which she founded in 1986.5 Through her work, Hamilton continues to inspire women and men alike to believe in their dreams and to pursue them fearlessly, despite all odds.

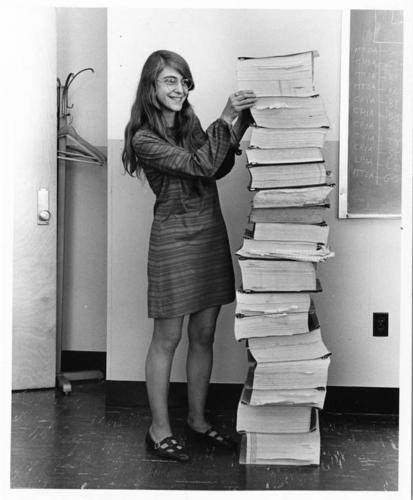

Margaret Hamilton standing next to the “Apollo” code she wrote

Source: NASA (https://www.nasa.gov/feature/margaret-hamilton-apollo-software-engineer…)

Sources:

- https://www.nasa.gov/feature/margaret-hamilton-apollo-software-engineer-awarded-presidential-medal-of-freedom

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Margaret-Hamilton-American-computer-scientist

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c_fDk1mFiW0

- http://news.mit.edu/2016/scene-at-mit-margaret-hamilton-apollo-code-0817

- http://htius.com/

Icons in Women's History - Virginia Woolf

“But for women, I thought, looking at the empty shelves, these difficulties were infinitely more formidable.”

Virginia Woolf’s seminal essay, A Room of One’s Own, was published in 1929, nine years after the ratification of the 19th amendment giving women the right to vote. It is still widely taught in college English classes across the country today, and for what purpose? Should not a change of law be all that women need to feel like their voice matters in the face of formidable difficulties?

Woolf begs us to closely examine the empty shelves of women. As she, and many before and after her have demonstrated, putting pen to paper in terms of the law only accomplishes so much. There lies a shift in social consciousness that must occur in order for policies to truly matter in the way they were intended. She brings to the forefront of the psyche the things women need to use their minds to their full capacity by practicing exactly what she preached: extensive use of her own mind.

As women, and humans, we still examine our empty shelves daily. Woolf inspires me to use my passion as a means to an end, even in times where the end is uncertain. The only certain way to make a better end for women is to engage the mind and show the world what we are made of, to step to the plate every day and work for exactly the things they said we could not do. For even if they continue to say we cannot, we must know that we can. It is not our place to demean others to bring ourselves up, but it is our place to put in the hard work to ensure those after us continue to work hard and with passion, in a setting where women are allowed to let their minds flourish, filling up the empty shelves.

“But I maintain that she would come if we worked for her, and that so to work, even in poverty and obscurity, is worthwhile.”

Icons in Women's History - Émilie Du Châtelet

Throughout history, there have been many women who helped pave the way for advancements in the arts and sciences, but did so without any formal recognition from their field. One such woman was Émilie Du Châtelet, an accomplished French mathematician, physicist, and philosopher. While many scholars have focused on her Du Châtelet’s relationship with Voltaire, a famous French Enlightenment historian and philosopher, Du Châtelet in her own right achieved many great feats that advanced scientific understanding of the principles of energy conservation and completed many studies in natural philosophy.

Born in 1706, Émilie was a bright and precocious child, much to her mother’s dismay but her father’s delight. Not only brilliant in mathematics and science, Du Châtelet also showed great interest in languages and spoke fluently in six different languages by age twelve. When denied access to higher education in the sciences, Du Châtelet instead entertained mathematicians and philosophers in her home, winning over their hearts and ultimately convincing her guests to let her study under them. Her mathematical mind made her particularly keen to gambling, a skill she used to pay for scientific books and equipment so she could continue her studies. Though her life was short (she died in 1749 at the age of forty-three), Émilie completed many works, including her own book on philosophy known as Institutions de Physique as well as a translation and commentary of Isaac Newton’s book on the basic laws of physics, Principia. Émilie’s commentary provided new insights into conservation law and kinetic energy and she completed it while she also cared for her three children and carried another pregnancy. Her companion Voltaire acknowledged Du Châtelet’s brightness and her significant assistance with his own book on Newtonian physics, Eléments de la philosophie de Newton. After her death, Du Châtelet’s contributions to physics heavily influenced great minds of the French Enlightenment and continue to generate interest in the scientific community today.

In a time where women were discouraged and some even prohibited from pursuing academia in topics “unfit for young ladies”, Du Châtelet overcame the adversity posed by her upbringing and society by holding true to her passions. Never did she allow her exclusion from scientific communities prevent her from growing her talents or achieving her goals. Du Châtelet’s brilliance was certainly impressive, but what inspires us now is her resilience and dedication in the face of those who stood in her path.

References:

https://plato.stanford.edu/ent

https://www.aps.org/publicatio

Icons in Women's History - Viola Davis

Viola Davis grew up poor and hungry in a rat-infested apartment with her two parents and five siblings. She and her sisters would wrap bedsheets around their necks to protect themselves from rat bites while they slept. Her pursuit of friendship and extra-curricular activities often centered around whether free food was available. Somehow, she discovered and pursued her love for acting in high school.

Ms. Davis earned scholarships to study theater—first at Rhode Island College and then at The Juilliard School. After completing her education, she started acting on Broadway. In 2001, Ms. Davis won a Tony Award for Best Featured Actress in a Play for her role as a mother fighting for abortion rights in King Hedley II. Then in 2010, she won another Tony award for Best Actress in a Play for her role as Rose Maxson in the revival of Fences.

Throughout her career, Ms. Davis also worked in TV and film. In 2015, she became the first African-American woman to win an Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series for her work as lawyer Annalise Keating in How to Get Away with Murder. She then won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her portrayal of Rose Maxson in the film adaptation of Fences in 2016. Ms. Davis is the only African-American woman to win a Tony, Emmy, and Oscar.

Ms. Davis decided to use her past to help others by raising money for the Hunger Is campaign, run by Albertsons Companies Foundation and the Entertainment Industry Foundation. Hunger Is aims to combat childhood hunger by providing funds to programs focused on combating childhood hunger. As of 2015, she had raised $4.5 million dollars for the campaign.

Ms. Davis is also an outspoken feminist: she gave a powerful speech on intersectional feminism at the Women’s March this year in Los Angeles, California. As a survivor of sexual assault, she spoke out for all the other women affected, especially those faceless women who don’t have the money, constitution, social stature, or confidence to speak for themselves.

Ms. Davis is an inspiration. She managed to transform her incredibly difficult childhood into an award-winning acting career. She has taken her personal obstacles and used them to help others who are struggling with the same issues. She is a voice for women and children everywhere.

Icons in Women's History - Fannie Lou Hamer

Fannie Lou Hamer grew up in poverty as a sharecropper in the rural Mississippi Delta. As young as six, Hamer worked the fields and was forced to leave her schooling behind after grade school. When her family made strides to get ahead, her father purchased two mules to help with the farm labor. Angry whites poisoned the mules as a warning: there were dangerous consequences for black people who tried to get ahead.

As an adult, Hamer was sterilized without her consent, while under anesthesia for a routine surgery. Non-consensual hysterectomies, or forced sterilizations, were commonplace for African American women at the time. This invasive, inhumane process propelled her into politics. Hamer is famously quoted saying, “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

In 1962, Hamer went to a meeting held by Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) activists, who aimed to sign up African American voters. This was the first time she learned that African Americans had a legal right to vote. Prompted by this meeting, Hamer and seventeen others attempted to register to vote, but only she and one other person were allowed to fill out the applications. Though she was literate, Hamer failed the literacy test, and upon returning home, an angry plantation owner forced her and her family off the plantation. Her husband was forced to finish the season there and left with nothing, after the plantation owner kept their car and possessions.

With nothing left to lose, Hamer threw herself into a life of activism. SNCC noticed her leadership potential and she began working for African American voting rights and desegregation. After being arrested at a sit-in, officers forced two African American inmates to brutally beat her. She later recalled that the men had been coerced into harming her, and did not blame them.

Hamer helped found the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) in 1964, which opposed the all-white democratic delegation at the Mississippi Democratic convention. It was there that Hamer gave a speech on the abuse that African Americans frequently endured, from beatings and lack of representation in government, to the lack of fundamental human rights and poverty. The convention responded by offering two seats to the MFDP members but no voting rights,an offer which Hamer declined. Her televised speech brought national attention to the African American struggle, and a year later, she ran for Congress.

Though she ultimately lost the bid, in 1968 the MFDP changed its name to the Mississippi Loyalty Democratic Party (MLDP) and Hamer got herself a seat at the Chicago national democratic convention. She took her seat with a standing ovation. She continued her work to uplift African American communities throughout her lifetime. The more opposition she faced, the harder she fought for social and economic equality, ultimately starting a farm that provided jobs to impoverished whites and African Americans.

In 1977, she lost her life to breast cancer. She is remembered for her tenacity and her use of song as a rallying cry for change.

Sources:

Fannie Lou Townsend Hamer, awomanaweek.com (last updated 2018), http://www.awomanaweek.com/hamer.htm.

Fannie Lou Hamer (1917-1977): Testimony Before the Credentials Committee, Democratic National Convention, American Radio Works (last updated 2018), http://americanradioworks.publicradio.org/features/sayitplain/flhamer.h….

Joan Johnson Lewis, Fannie Lou Hamer: Civil Rights Movement Leader, ThoughtCo (last updated March 18, 2017), https://www.thoughtco.com/fannie-lou-hamer-3528651.

Sarah K. Horsley, Fannie Lou Hamer, Fembio Notable Women International (last updated 2018), http://www.fembio.org/english/biography.php/woman/biography/fannie-lou-….

Freedom Summer: Fannie Lou Hamer, PBS (last accessed March 13, 2018), http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/freedomsummer-hamer/.

Icons in Black History - Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth’s legacy as a pioneer in both the women’s rights movement and the anti-slavery movement is well established worldwide. She used her voice to advocate policy for women and Black people. She spoke tirelessly with politicians and appeared at numerous influential conventions to spread awareness and her message. Sojourner’s blunt “tell it like it is” oratory style was particularly effective to influence change and bring attention to her concerns. She was unconventional and daring. Sojourner not only navigated spaces that were unwelcoming to Black women, but she also left an impression in those spaces that continues to shine through nearly two hundred years later.

Sojourner overcame the brutal realities of chattel slavery. She was born in New York to enslaved parents around 1799. Sojourner reportedly had five children. But, by her own account, she gave birth to thirteen children and her slave masters sold most of them into slavery. New York law mandated Sojourner’s manumission in 1827. Although her owner promised to free her a year earlier he denied granting her emancipation in 1826. This denial emboldened Sojourner to escape the plantation with her youngest daughter. Soon after her escape, she discovered that her five-year old son had been sold to an Alabama slave owner, presumably to evade New York law requiring his manumission at twenty-one years old. Devastated, Sojourner petitioned her former mistress and other individuals for his return. But, all of her requests were denied, as the motherhood of Black women was not a legitimate concern.

Sojourner fought as a fearless advocate for her son’s freedom and the ability to parent. It was a revolutionary endeavor considering that the laws at the time decreed that enslaved women had no enforceable right to care for their children. Enslaved persons also lacked standing in many jurisdictions to bring claims before courts. However, eventually Sojourner’s efforts prevailed and lawyer eventually secured a writ ordering the return of her son back to New York for her custody and care. Fortunately, Sojourner’s advocacy did not stop there, it continued and birthed her quest for equal rights for women and Blacks.

Surpassing illiteracy, Sojourner’s straightforward, plain-spoken, and sincere orations were highly effective. Sojourner’s famous “Ain’t I a Woman” speech was more than a speech supporting the feminist movement of the time. She delivered her speech at the 1851 Women's Rights Convention following speeches from white male religious leaders supporting the subordination of women. More interestingly, she delivered the short and powerful speech under the hesitancy of many white feminists that felt her presence would take away from their cause. It was a direct call-out and criticism of the white male power structure and denial of Black womanhood. It highlighted the intersectionality of being both Black and a woman in a society that considered her to be less than a woman because she was Black and not deserving of basic rights because she was a woman. Unflinching, Sojourner once bore her breasts to emphasize her womanhood. She also challenged anti-slavery discourse for its exclusion of the rights of Black women. Sojourner’s legacy of activism and dedication supersedes her brutal beginnings and her striking influence on feminist and abolitionist policy cannot be denied.

Icons in Black History - Judge Addeliar Dell Guy III

Black History encompasses far more than the month of February can contain, but that does not mean that we all should not use February to remember, recognize, and retell stories of the important African-American men and women who have shaped our lives and communities.

For me, one such person is my grandfather, Addeliar Dell Guy III, or Judge Guy as he was commonly known here in Nevada.

Judge Guy came to Nevada by way of Chicago in the early 1960’s. Ted Marshall, the District Attorney at the time, persuaded him that a real difference could be made by moving to Las Vegas and practicing law. At the time, Las Vegas was beginning a long overdue diversity initiative, or it should be said a group men and women were pushing Las Vegas forward: Judge Guy became one of those individuals.

After passing the Nevada bar, Judge Guy became the first African-American Deputy District Attorney in 1966. Judge Guy would go on to become the first Chief District Attorney, followed by Governor Michael O’Callaghan appointing him to Eighth Judicial District Court, Dept. XI, in 1975: making Judge Guy the First African-American Nevada state court Judge. Judge Guy would serve on the bench for over 20 years, rising as high as an alternate judge on the Nevada Supreme Court.

Along with a remarkable amount of firsts, Judge Guy was an active mentor for men, women, and attorneys in Nevada. In 1981, Judge Guy along with, Robert Archie, Andras F. Barbero, B. Jeanne Banks, Marcus Cooper, James Davidson, Michael Allen Davis, David Dean, Booker T. Evans, James O. Porter, Johnnie B. Rawlinson, Dan Winder, Arthur L. Williams, Jr. and Justice of the Peace Earle W. White, Jr founded the Las Vegas National Bar Association Chapter (LVNBA). Judge Guy, also, was a founding member of the Las Vegas Theta Pi Lambda Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc in 1964.

While it is impossible—for me—to write how much Judge Guy influenced (and still influences) countless attorneys, future attorneys, and people in our the Nevada community, it is possible to write that he left a lasting impact on Las Vegas, the state of Nevada—its citizens, and myself. It is an honor, therefore, for me to remember, recognize, and retell a piece of the Judge Guy story during Black History Month.

Icons in Black History - Maya Angelou

“My mission in life is not merely to survive, but to thrive; and to do so with some passion, some compassion, some humor, and some style.” Maya Angelou’s words continue to reverberate in my mind. Her words serve as a road map in how we should structure our daily actions. Life is not merely pulling through Mondays or getting through the week. Everyone should strive to live their life to the fullest. One should find ways to show creativity in personal areas of expertise. It is this kind of introspection that makes Maya Angelou, and her influence, timeless.

Maya Angelou was born on April 4, 1928 as Marguerite Annie Johnson in St. Louis, Missouri. She died on May 28, 2014. Maya Angelou was a woman of numerous talents. She is well known for her striking poems, “Caged Bird” and “Still I Rise.” The former is an artistic work reminding people that even with barriers and oppression, one does not lose sight of freedom and hope. The latter poem conveys the message that despite any trials or tribulations in life, nothing can keep one down. Her writings manifest the intrinsic beauty in poetry, as she conveyed her personal life experiences into utterly captivating verses.

This multitalented poet was also a Civil Rights activist, an actress, screenwriter, and dancer. Adversity was no stranger to Maya, but she knew how to overcome hardships. While growing up, she experienced a traumatizing incident that left her mute for years. Later, in California, she became the first black female cable car conductor. She temporarily held this job before having her son at age sixteen, which she then worked various jobs to support him. Still, she overcame struggles and worked persistently in her life.

For Maya, adversity wasn’t something that limited her. In fact, she seemed to thrive in it. She won award nominations for her acting, and had her screenplay produced, which she was the first black woman to do so. Despite any barriers, Maya Angelou reminds her audience that no matter your beginning, you too can overcome any hardship in life; everyone gets knocked down in life, but it is how we get back up that defines us.

Sources:

Maya Angelou, A&E Television Networks (last updated Jan. 18, 2018), https://www.biography.com/people/maya-angelou-9185388

Jan Bruce, The 3 Lessons Maya Angelou Taught Us About Coping, Huffpost (06/12/2014 09:53 am ET), https://www.huffingtonpost.com/mequilibrium/maya-angelou-legacy_b_54793…

Icons in Black History - Thurgood Marshall

The story of Thurgood Marshall is common to many and even more common to those within the legal community. Marshall is a pillar in the history of the civil right movement and within black history. Mr. Thurgood Marshall is most notable for becoming the first African-American to take a seat on the Supreme Court of the United States. However, that is only a portion of his legacy as Marshall made his impact on history long before he began his 24-year service on the Supreme Court.

Long before he ascended to the Supreme Court, Thurgood made his mark in history as a civil rights attorney. Thurgood Marshall graduated at the top of his class and under the tutelage of Charles Houston—the Dean of Howard Law School—Marshall discovered his gift to use his legal expertise to combat racial discrimination and widespread segregation.

In fact, his first order of duty as a newly minted attorney was suing the Maryland University Law School. Prior to attending Howard Law School, Marshall applied to attend the Maryland University Law School, a racially segregated school. Despite being overqualified, Maryland University Law School denied Marshall admission on the sole basis of his race. Hence, he was forced to travel several miles to attend Howard Law School in Washington, D.C. instead. After Marshall graduated from Howard Law School, Maryland University Law School remained racially segregated. Marshall, now an attorney in the Baltimore Branch of the National Association for Colored People (NAACP), defended another well-qualified candidate, Donald Murray, who had been denied entrance to the Maryland University Law School. Marshall skillfully used the “separate but equal” doctrine—the doctrine used to justify racial segregation—to his advantage in his argument. His reasoning was simple: Maryland University Law School’s racial segregation policy violated the “separate but equal” doctrine because the state of Maryland failed to offer a comparable, non-segregated law school. In 1936, the Maryland Supreme Court ruled in Marshall’s favor and Murray was admitted. This was first of a long line of cases that Marshall would continue to use to undermine racial segregation in the United States.

Marshall claimed his first victory from the United States Supreme Court in Chambers v. Florida (1940). Marshall successfully defended four African-American men who—after each were severely beaten by law enforcement—confessed to murder and were subsequently convicted. In Smith v. Allwright, Marshall gained a significant victory, persuading the United States Supreme Court to strike down the Democratic Party’s use of white-only primary elections. Marshall’s most notable civil rights victory was the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. Through this case, Marshall successfully challenged the “separate but equal” doctrine established by the Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson. In May 1954, the Supreme Court unanimously overruled the racial underpinnings of the “separate but equal” doctrine.

Accordingly, Thurgood Marshall established himself as one of the most prominent and successful attorneys in America. His legacy not only shattered racial segregation throughout the nation, but also set an example for future generations of attorneys. Marshall’s story has persuaded countless African-Americans, including me, to pursue a career in the law. Moreover, Marshall was instrumental because he not only helped make it possible for African-Americans to attend universities and law schools throughout the country, but set the principle example of what it takes to be successful advocate. Upon passing the bar exam, Marshall did not waste any time to put his law degree to use. He recognized his greatest task as an attorney was embracing his role as a social engineer. Marshall realized his duty—to effectuate change—was not limited by his young age or experience. Rather, he set an example, he sought mentorship, he polished his craft, and, most notably, he used his legal prowess to battle injustice. Accordingly, Thurgood Marshall serves as the standard of excellence every attorney should strive toward. In the midst of a racially divided country, Thurgood marshaled the law to the aid of his people, and even today, we still enjoy and reap the benefits of his legacy.